1 Economic function of the entrepreneur

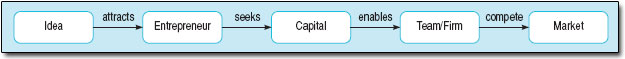

Broadly, entrepreneurs have two vital roles to play in the economy (1) to introduce new ideas and (2) to energise business processes. Strictly speaking, the term entrepreneur, which derives from the French words entre (between) and prendre (to take), referred to someone who acted as an intermediary in undertaking to do something. The term was originally used to describe the activities of what today we might call an impresario, a promoter or a deal maker. The entrepreneur first made an appearance as a distinct economic concept in France, twenty years before the ‘father’ of economics, Adam Smith published his Wealth of Nations in 1776. Richard Cantillon, an Irishman living in France, suggested in 1756 that the entrepreneur was someone prepared to bear uncertainty in engaging in risky arbitrage buying goods and services at a certain (fixed) price in one market to be sold elsewhere or at another time for uncertain future prices, usually in other market (though, throughout economic history, hoarders or traders who try to ‘corner’ a market have sought super-profits in the same markets when short supplies send prices rocketing upwards). This concept of entrepreneur as arbitrager is still relevant today but was clearly influenced by the dominance at that time of trade as the chief means for accumulating new wealth and capital. Manufacturing and trade dominated Britain's heyday in Victorian times whereas today, as the case studies show, it is technology, knowledge and services that provide most, though by no means all, new entrepreneurial opportunities. In other words, entrepreneurship exists in its context as Figure 1.

Here, the role of the entrepreneur is to conceive a business idea in terms of an innovation to be brought successfully to the market and to find the wherewithal to make this happen. The entrepreneur does not necessarily need to have the design, production or delivery skills (this is the function of the firm) nor to shoulder all or most of the risk (this is often assumed by the providers of finance or investors). Indeed, the notion of the entrepreneur as a risk-taking trader, began to be challenged early on by the view of the entrepreneur as an adventurous self-employed manager capable of combining, to personal advantage, capital and labour. It is interesting to note that in France today the entrepreneur is a more generic term mainly referring to small property developers and owners of small construction firms. It would be wrong to state that the element of risk-bearing has completely disappeared from the modern concept of the entrepreneur. The successful management of risk is an important entrepreneurial attribute. However, it does seem true that a swift perception of opportunities and the ability to coordinate the activities of others emerge as the more central economic skills of the modern entrepreneur.

Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter (1934), who has had a seminal influence on entrepreneurship, as well as innovation, placed the entrepreneur at the centre of his theory of economic development. Schumpeter defined the entrepreneur simply as someone who acts as an agent of change by bringing into existence a ‘new combination of the means of production’. New combinations include process, product and organisational innovations. The means of production includes capital, equipment, premises, raw materials, labour and, in recent times, information. Currently, knowledge has been added to the list as the indispensable ingredient for business success in the new millennium.

The essence of Schumpeter's approach is that entrepreneurs are competitive and always strive to gain an edge over their competitors. When they begin to consolidate and slow down, they revert to being ordinary managers and, in Schumpeter's terms, are no longer entrepreneurial. Thus attitudes to growth and the actual attainment of growth are essential elements of the concept of entrepreneurship. The attainment part of the concept, of course, implies a high level of managerial competence in all the five stages in Figure 1 and a high competence in social and commercial interactions outside the firm with other firms, regulators and, above all, customers and consumers. This implies that entrepreneurial firms that innovate successfully and encourage new innovations are likely to be different from most other firms. They appear to be more open and supportive of different opinions and ideas. If you are developing your own idea as part of an organisation (or if you feel that your idea will need the combined efforts of a firm for its implementation), Activity 1 will help you identify where you need to develop and negotiate support both inside and outside the firm. The art of negotiation is a key entrepreneurial skill.

Activity 1

Referring to the characteristics of successful innovation, complete the Characteristics of the entrepreneurial firm checklist.

Before starting this activity you should determine where you are going to record your notes. You may choose to maintain a paper notebook. You may, however, prefer to record your thought electronically either by using a word processing program or by using the OpenLearn Learning Journal facility.

Consider the ideal firm for bringing your idea to market (or if your ideas have not yet crystallised, an enterprising group or firm of at least two other people you know). Make a note about the purpose of the firm or team before you answer the questions.

Try to answer the following questions (pausing for reflection if you need to.) If the answer is ‘Yes’ write a brief example. If the answer is ‘No’, write the main reason. If you are uncertain about the question click the question mark and an additional explanation of what is being asked will be revealed.

If you answered ‘Yes’ to five or more questions and were able to give clear examples it is most likely that the firm you have in mind is innovative and encourages both creativity and a sound approach to business. If you answered ‘No’ to five or more questions, your proposed innovation may not recieve sufficient support from such an organisation.

The characteristics of entrepreneurial firms that are successful at launching innovations have been widely studied and are reflected in the questions asked in Activity 1. However, at this stage you may be a long way off starting, or helping to start, your own firm. The checklist should serve as a useful tool for gauging the innovative support from your current situation and as a guideline for the sort of atmosphere that needs to develop in a firm in order to maximise its entrepreneurial potential. When faced with very real resource constraints, maintaining motivation to set up and run such a firm can be very tough. The main motivation for entrepreneurs to overcome the barriers of economic pressure and uncertainty, according to Schumpeter (who was writing in the 1930s), were the prospects of upward social mobility into the capitalist class. At the start of the 21st century, with the almost universal dominance of market-based economic systems and a hugely increased middle class, the need to cope with the direct and indirect threats of ‘globalisation’ is now often cited as the spur to innovation. For others, economic survival or the chance to create something of value are the driving motivators. Whatever the personal ambitions of entrepreneurial small firm owners, their role in introducing innovations and in improving overall economic development and efficiency is important.

Basically, the concept of development from an economic viewpoint means the growth of goods and services in an economy usually measured in total or per capita rates of growth in all goods and services, known as the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or the Gross National Product (GNP) when nationally owned overseas goods and services are included. In advanced industrial economies such as Britain, France, Germany and so on, policy objectives tend to be targeted on improving economic performance rather than development per se. As an alternative to an economic approach, one of the best known psychologically based economic development models that is still very influential, David McClelland's achievement motivation model, pays less attention to structural factors while the psychological determinants of economic behaviour are more strongly emphasised:

Some wealth or leisure may be essential to development in other fields the arts, politics, science, or war but we need not insist on it. However, the question why some countries develop rapidly in the economic sphere at certain times and not at others is in itself of great interest, whatever its relation to other types of cultural growth. Usually, rapid economic growth has been explained in terms of ‘external’ factors favourable opportunities for trade, unusual natural resources, or conquests that have opened up new markets or produced internal political stability. But I am interested in the internal factors in the values and motives men have that lead them to exploit opportunities, to take advantage of favourable trade conditions; in short, to shape their own destiny.

McClelland's preferred entrepreneurial motivator, the need for achievement or nAch as it is usually abbreviate – ‘a desire to do well, not so much for the sake of social recognition or prestige, but to attain an inner feeling of personal accomplishment’ – is a more psychologically-based theory. McClelland himself summarised an alternative economic development theory as ‘a society with a generally high level of nAch will produce more energetic entrepreneurs who, in turn, produce more rapid economic development’. However, McClelland was quite disparaging about the profit motive as the mainspring of entrepreneurial activity:

Since businessmen had obviously shifted their concern from intrinsic worth to money worth, Marx and other economists endowed man with a psychological characteristic known as the ‘profit motive’. The capitalist, at any rate, was pictured as being driven by greed, by the necessity of making money or keeping up his rate of profit.

That such an assumption is a typical oversimplification of rational or armchair psychology has recently begun to be realised by historians in particular who have studied the lives of actual business entrepreneurs in the nineteenth century. Oddly enough, many of these men did not seem to be motivated by a desire for money as such or by what it would buy.

Box 1 Wall Sreet (1987) Gordon Gekko: Address to Teldar Paper Stockholders

Teldar Paper has 33 different vice presidents, each earning over $200,000 a year. Now, I have spent the last two months analyzing what all these guys do, and I still can't figure it out. One thing I do know is that our paper company lost $110 million last year, and I'll bet that half of that was spent in all the paperwork going back and forth between all these vice presidents.

The new law of evolution in corporate America seems to be survival of the unfittest. Well, in my book you either do it right or you get eliminated.

In the last seven deals that I've been involved with, there were 2.5 million stockholders who have made a pre-tax profit of $12 billion. Thank you.

I am not a destroyer of companies. I am a liberator of them!

The point is, ladies and gentleman, is that greed – for lack of a better word – is good.

Greed is right.

Greed works.

Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit.

Greed, in all of its forms – greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge – has marked the upward surge of mankind.

Activity 2

- Do you think that profit maximisation is the main motivation to entrepreneurial behaviour?

- Does profit have to be the main motivation of a successful business owner?

- What alternatives or additional motives can you identify?

Clearly, the ‘oversimplification’ of the profit motive determining economic development has survived longer than McClelland believed it would and remains a central pillar to current business and economic analysis. Other motives include the need for autonomy, to ‘be my own boss’, to support a preferred lifestyle, to provide security for the family, to achieve social status and so on. Nevertheless, earning profits and making money also feature as important motives and the potential profitability of a new product is still usually the acid test of its likely viability. And well know entrepreneurs to the press and public are usually very successful and very rich business owners.