4 The eBay phenomenon – what it means

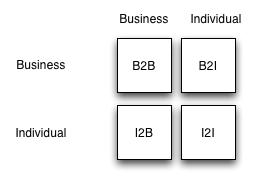

Writers on e-business group Internet processes into four categories, using this grid:

Business-to-Individual (B2I) is the conventional e-commerce sector. The online bookseller Amazon is a leading example. Online auction services like eBay fall in the bottom right-hand sector – Individual-to-Individual (I2I) – because they facilitate transactions between individuals and derive their revenues solely from fees paid by participants in the virtual marketplace that they provide.

eBay has grown phenomenally since its launch in September 1995. It now has 105 million registered users, 328 million listings, gross sales worth $8 billion, revenues of over $750 million and operates in 28 countries. In almost all of its major markets it is the biggest e-commerce site. Its stock market valuation in April 2004 was in the region of $53 billion.

This kind of growth and market penetration could only have been achieved if the company was offering a service that customers really wanted. Like a handful of other Internet ventures – Amazon and Google are the ones that come to mind – eBay has changed the world in a significant way by making possible what had hitherto been difficult or impossible. People sometimes derisively describe eBay as ‘a global car-boot sale’, but in a way that is both true and the main reason for its success. It provided people with a way of buying and selling that up to then had been available only in a small-scale, localised way.

eBay has also had an impact on the economies of the countries in which it operates by creating a kind of economic ‘ecosystem’. For example, many small traders who had previously operated as stall-holders or shopkeepers now operate exclusively on eBay, thereby saving on rent and other expenses. It has changed the way in which craftspeople market their wares. It provides an inexpensive route into e-commerce for small companies who might balk at running their own online retailing operations. And it has provided a mechanism for buying and selling specialised, obsolete or obscure items which would otherwise go untraded.

Increasingly, eBay has affected bigger companies too. Sun Microsystems, for example, generates sales of the order of $1 milliion a week by selling equipment via auctions. The company offers on eBay the servers that haven't sold as well as expected and which they need to sell to free up warehouse space. Sun also auctions last-generation products that might otherwise be retired because of technological advancements – e.g. when Sun moved from computers with CD-ROMs to ones with DVDs. Other large companies are turning to online auctioneering for similar reasons.

The explosive growth of eBay has had interesting side-effects. For example, it provides a kind of weather-vane for how the economy is doing. After the dot-com crash in 2001, for example, observers noted a marked increase on eBay of expensive office chairs of the kind favoured by technology start-ups. At the beginning of 2003, the newspaper USA Today noted that ‘BMWs, Gucci and Prada reigned supreme on eBay. All were among the 10 most-searched terms. Last year, the No. 1 search was for Gucci.’ But at the end of 2003, the picture was different. ‘The most-searched items have shifted to Fords, anything pink…, and gold (the kind you store in a wall safe as a hedge against geopolitical or economic disaster).’ This is significant, the paper maintained, because ‘no executive decides what eBay sells. Instead, millions of individuals post items on the Web site in response to shifting nuances in the marketplace. Because it is so fluid, the site captures the collective mood and unique extremes of the 86 million people who use it.'

Another measure of eBay's influence is the emergence of an entire subculture of companies and services which are parasitic on (or symbiotic with) it. For example, there are organisations like eSnipe which place bids for subscribers during the last few seconds of the auction, a practice known as ‘sniping’ in the online auction world. eSnipe reduces bidding wars by masking interest in auction items until the last possible moment. Because auctions on eBay take between 3 and 10 days to close, ‘emotional’ overbidding can start soon after the auction opens and last until the auction closes, instead of mere minutes as is the case in traditional – offline – auctions. Similarly, there are companies that will make eBay listings for customers and handle the entire transaction. Customers drop off goods to these eBay-service companies, which then do all the work involved in auctioning them online. When the goods are sold, the ‘drop-off’ service takes a fee and then pays the remaining proceeds to the original vendor.

But it's not all plain sailing. An open, online auction system is also vulnerable to abuse. There have been widely publicised cases of fraud on eBay. One celebrated case involved the sale of over US$400,000 in gold and silver coins and bullion, which were allegedly never delivered to winning bidders after payment was received. Another famous case resulted in two men pleading guilty in a Californian federal court to cheating eBay users out of $450,000 over two years by bidding on their own auctions to drive up prices. There have been numerous, smaller and less-reported cases – for example, a company that sold laptop computers and traded without complaint for a considerable period, building up an impressive ‘profile’ in the process. But when it got into financial difficulties, it kept taking money from bidders but stopped shipping the goods. And there are regular allegations that some items offered for sale in eBay are, in fact, stolen property.

For obvious reasons eBay is acutely sensitive on the subject of real or alleged fraud – for the system to work, it has to be trusted by those who use it. The company says that fraud constitutes ‘less than 0.01 per cent of all transactions’, and claims to investigate complaints quickly and rigorously. It also offers various ways of resolving the disputes and conflicts that are inevitable when millions of individuals are buying and selling. It directs complainants to a third party Dispute Resolution service like SquareTrade to help buyers and sellers sort out disputed transactions and says that ‘SquareTrade has an excellent reputation of resolving disputes quickly and fairly.’ The company runs its own investigation unit called SafeHarbour, and runs a ‘Buyer Protection Programme’ which allows buyers a reimbursement of up to £105 if they are the vicims of fraud.

The vast majority of eBay transactions are straightforward; the service would not have grown so quickly if its users did not trust it. But in the end, the best rule for anyone buying or selling is to check out goods and the other party to the transaction. If in doubt, contact the seller directly by email and check out his/her profile. And if you have concerns, simply refuse to bid. The old Latin adage caveat emptor (buyer beware) still applies in Cyberspace!