2 Design and innovation 1: the plastic kettle

2.2 Who dares wins?

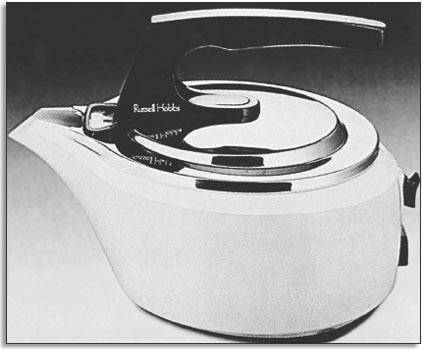

As sales were so buoyant, does this indicate that the new plastic kettles were an immediate runaway success? Well, actually no. The early plastic kettles quickly became shabby, primarily because the polymers used absorbed traces of fats present in a kitchen environment and were easily discoloured by sunlight. Also, the surfaces were easily scratched and the fashion-driven colours dated quickly. Even worse, the polymer tainted the water during boiling, giving it a distinctive taste. The first mass-produced polymer kettle was launched in 1978 by Russell Hobbs. It was called the Futura and it was a failure (Figure 9). Not only did it suffer from the disadvantages stated above, but it also took a long time to boil owing to its small heating element, which was demanded by the need to minimise the potential fire risk.

There were technical problems. The Futura was expensive to produce and because it had no lid (it had to be filled via the spout) users were suspicious of the cleanliness inside the kettle. It was killed off because a high number of kettles were returned to the manufacturer. Furthermore, in the company's culture, polymers then became associated with failure, which hindered any subsequent in-house innovation with plastics. It is interesting to note that this design takes its form and general arrangement from the stainless steel kettles with which it was in competition; the innovation was in the use of a new material rather than the shape. It was not until after this that another company launched the first plastic ‘jug’-shaped kettle which did so much to invigorate the kettle industry.

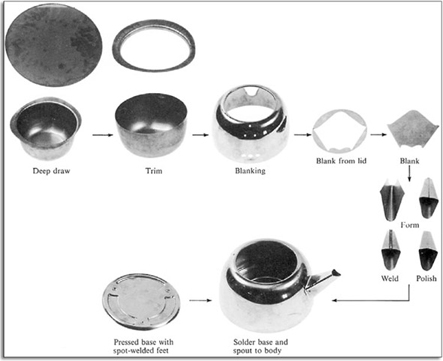

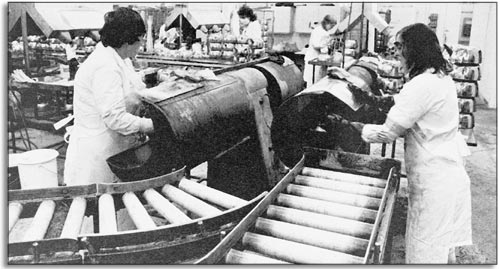

Although the ‘demand’ side of the supply-and-demand picture was problematic at this time, radical changes can be observed in the supply of plastic kettles. The increasing availability of cheap plastic mouldings together with the necessary heating elements, switches and cords meant that it was possible for many new companies to set up in business assembling and marketing plastic kettles. The significant investment required for the fabrication of stainless steel kettles did not apply to these new assemblers, and the number of companies producing plastic kettles increased tenfold. They joined established companies such as Russell Hobbs who had their own in-house design, manufacture and marketing capability. Figure 10 illustrates the expensive stages involved in the production of a stainless steel kettle; Figure 11 shows part of the production line at Russell Hobbs where metal is stamped, cut, bent, soldered and polished: processes that require a skilled workforce.

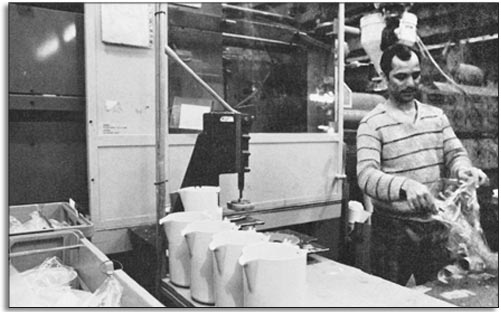

By comparison the production of a plastic kettle body is an unskilled process. One worker takes the plastic kettle body from an injection moulding machine (into which molten plastic is forced into a mould under pressure, and where it cools and solidifies into the desired shape), snaps off the sprues (residual projections resulting from solidification of plastic within the mould's feed channels), and puts the kettle body in a bag (Figure 12).

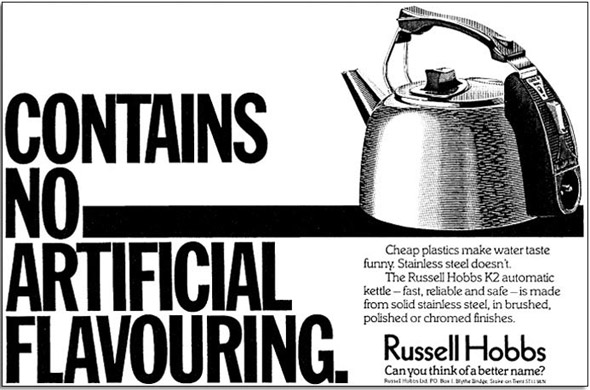

After an enthusiastic welcome for the innovation, the market displayed some resistance to plastic kettles. They were not perceived as good value for money, and word soon spread. However, the supply was rapidly increasing, thus driving the price of plastic kettles down. It was, and still is, very convenient to be able to boil water safely and quickly and the manufacturers knew there was a huge market if they could overcome the problems. Materials science soon solved the problem of the unpleasant tainting of the water during boiling, and as the market grew so the price of plastic kettles tumbled. Consumers were faced with some stark realities. They could purchase a metal kettle, which would undoubtedly have a long life, but at a considerably higher initial price than the plastic kettle. Alternatively, they could buy a new plastic kettle, add the status of a modern bright object to their home and replace it, if necessary, in a few years because of the cheap price. In spite of some companies continuing to promote the stainless steel kettle (see Figure 13) the plastic kettle won out.

Sales of plastic kettles continued to increase and manufacturers invested in the victor in order to secure for themselves a share of this lucrative market. New shapes, colours, surface finishes and styles of applied decoration appeared, but the real influence on demand seems to have been the shaping of the kettle body in the form of a jug.

It is not at all certain that anybody really benefits by changing the kettle shape from a pot to a jug but it has become the standard form for electric kettles today. Some advocates point to the ability of jug kettles to boil smaller quantities of water and thus to address the needs of those users who want to make one or two hot drinks at a time. This is achieved because the tall, thin jug kettle requires less water to completely cover its element. Clearly this has potential benefits for whoever pays the electricity bill and for the environment, but research has shown that most users continue to put as much water into a jug kettle as into a stainless-steel kettle!

The first successful plastic kettle was jug-shaped. It was designed by a consultancy called Action Design in 1979 and was produced by Redring, a company experienced in manufacturing the heating elements but new to the kettle market. In 1981 the Redring jug kettle saw more than a quarter of a million sales in Britain and together with export orders, contributed £16 million to company turnover. As with other contemporary plastic kettles the material and technical components were not ideal but its success in the market was observed by other manufacturers and it inspired the search for better polymers and technical improvements.

Exercise 1

How did the first polymer kettle compare to existing metal kettles in terms of:

- looks,

- cost,

- boiling time,

- taste of the water,

- durability.

Answer

- The shape of the Futura was the same as for the conventional kettles; the polymers allowed brighter colours to be used, though.

- The polymer kettle was cheaper.

- The heating element had a lower power, for safety reasons, so the water took longer to boil.

- The polymer used in the Futura gave the water an odd taste

- The polymer had a shorter lifespan, as the colours faded and the kettle began to look shoddy.