6 Design and innovation 3: the Brompton folding bicycle

6.6 The first production run

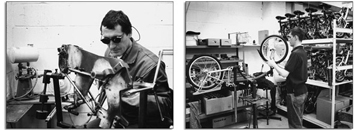

6.6.1 The factory opens

Let's return to the story of the development of the Brompton. Because Andrew Ritchie could not sell his idea, he decided to set up his own factory to manufacture the bicycles. He borrowed money from friends (the interest on the loans was a bicycle) to build 30 bicycles and 20 for sale.

After the increasing complications of the prototyping stage, manufacturing constraints become a powerful influence on the designer:

The main tube was positioned higher and a simpler bought-in offset hinge replaced the purpose-built tube hinges. This forged hinge, which was critical to the Brompton's development, was from France. So, detailed design changes were made to the hingeing system with some benefits to compactness resulting from positioning the hinge higher in the frame.

The telescoping seat pillar was dropped, becoming a single tube, and the frame was braced with a small diagonal cross-beam to give it extra stiffness.

6.6.2 Batch production

After the first 50 I got a small-firm government loan to produce batches of 50 bicycles; 400 in a year and a half.

Designing and manufacturing low-cost tooling was a harder job for Ritchie than designing the bicycle. There are many design routes to producing a lighter frame or a more easily manufactured frame that are not available to a small batch manufacturer. He had to use soft, mild steel for the main tube as he could not bend stronger alloy steel, and the main tube had an aesthetically ugly kink from the bending process. Plastic parts were machined from the solid and metal plate was drilled, cut and bent. The process is essentially scaled-up craft production.

During this period Ritchie learned from customers, and from riding his own bicycle. Indeed, sometimes detailed redesign was necessary in the light of problems and failures brought to his attention by users. The business remained vulnerable, although there was helpful press exposure (see Kew for a ride).

6.6.3 Mass production

In 1981 the French manufacturer of forged hinges discontinued production so Ritchie stopped batch production and wrote a Business Plan. After a hiatus of five years, in 1986, Ritchie eventually raised £90,000, half of the money he needed to go into mass production, from a customer, friends and family, and went ahead anyway.

The drive to design for manufacturability continues apace. A tool was designed to curve the main tube, so removing that kink. At the time of writing, 2000, a power press allows the use of a higher specification of steel for the main frame member. The hinges were machined from the solid until expensive forging tools could be bought in 1987. Ritchie is working on removing the skill from the manufacture of hinges.

Kew for a ride

From The Standard, Wednesday 3 February 1982, p. 19.

At 8.00 a.m. today, as always, Andrew Ritchie arrived at work on his bike. Mr Ritchie works at Kew. He has a workshop there and he built the bike he arrived on in the workshop.

A most remarkable bike it is too. It takes a few seconds to fold it up into a neat package less than 2 ft square which you can pick up and carry anywhere.

No other collapsible bike in the world, says Ritchie, collapses so totally and so easily. And it is just as simple to un-collapse it into a bike again.

Ritchie, an old Harrovian who read engineering at Cambridge, is 35 and says he is appalled by the amount of his life he has already given to this bike.

He had the idea at the beginning of 1976, but it wasn't until early last year that he was able to move into the workshop at Kew and put the bike into production.

He had orders for 30 bikes, mostly from friends and friends of friends. These were made and delivered by last March and, to his great relief, they brought in orders for 20 more.

By the time these were made another 30 orders had come in and there was some welcome help from HMG in the shape of a Small Firms Loan Guarantee.

So this particular small firm stays bravely afloat in these choppy seas, an example to us all.

It currently has a workforce of two – Patrick Mulligan, brazier and Andrew Ritchie, managing director and assembler – and this will increase as orders come in.

Meanwhile there are 56 Bromptons – that is what the bike is called – on the road now and 24 more ready for delivery and I can report that Judge Abdela has been seen arriving at the Old Bailey on one, that Lord Fraser of Tulley-Belton, the Scottish Law Lord, rides one, and that Ritchie's bike, No 7 from the production line, got him from South Kensington to Kew and back all through the blizzards.

It is, of course, an expensive way of making a bike, this, and each one costs £195 by the time you have added VAT. But they are extremely slick little bikes, and with only 80 made so far, think of the rarity value.

A special pedal is used on one side of the bicycle. The pedal folds away, so that it does not project from the folded bicycle. This adds £33 to the current (2001) price list (Figure 58). The pedal on the other side does not fold, and nestles in a tangle of spokes and tubes when the bicycle is folded.

The craft route to producing the pedal involves 64 operations. The company bought a piercing and blanking tool for £3500 in 1991 to reduce these operations. All the earlier prototypes and the first batch had a folding crank.

It takes 21 minutes to braze the rear frame. The company is investing in an automatic brazing system for the main frame.

We spend 25 minutes inspecting the bicycle after production and listen to our customer's problems carefully. We have a fatigue rig and keep a constant watch on the details of supplied items. In the early days I sent a £3000 order back to a supplier who did not use a radiused milling cutter.

6.6.4 Testing

Ritchie cycles regularly, so still tests ideas and changes. During summer 2000 Ritchie was assessing low rolling resistance tyres.

Gearing was always a problem. To most manufacturers the folding bike is a bottom-of-the-range product. We wanted proper gearing using a bigger-than-average chainwheel, so at various times we became involved in making gears, for example a 13 tooth rear gear. And we had problems with broken teeth. Things are better now. We use the 3 and 5 speed Sturmey Archer hub for gears.

We have resisted the complication of Derailleur gears. All that extra complication is against the philosophy of the design. Perhaps we could sell another thousand bicycles. It's what the market wants. It's a luxury, but we do not respond.

You can buy a Brompton bicycle, named after The Brompton Oratory, for about £500. Andrew Ritchie won a Queen's award for export achievement in 1995. Not at all bad for a company that, literally, started under the railway arches.