2 Entrepreneurial qualities

It is now widely accepted that, apart from the start up phase, most small firms in Europe are more concerned about survival rather than growth and relatively few are especially entrepreneurial (Gray 1998). Consequently, a lot of research in this field has focused on finding the characteristics that set entrepreneurs and their firms apart from others. Elizabeth Chell (1985, 1999), a social psychologist, has examined numerous psychological trait-based approaches and concluded that, whilst psychological aspects such as ‘entrepreneurial intention’ and the ‘ability to recognise opportunities’ are strongly linked to entrepreneurial behaviour, the context in which the entrepreneur operates is also very important. Entrepreneurship reflects complex interactions between the individual and the situation, which has to be dynamic because business situations are always changing.

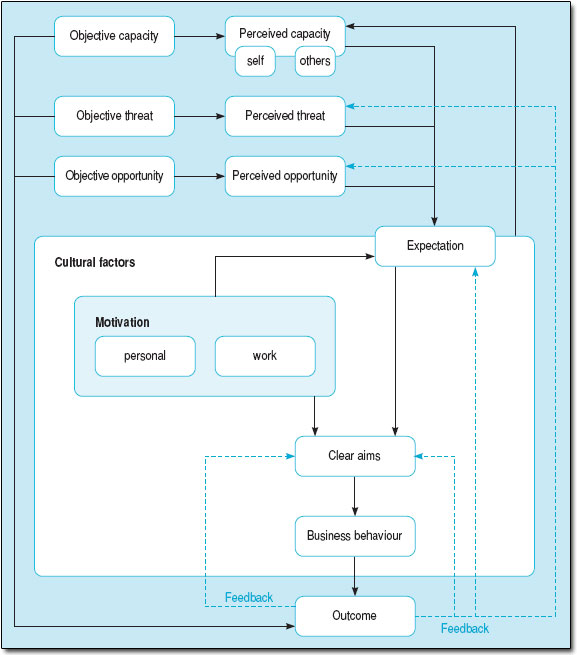

Perceptions and judgement are, therefore, key elements in this process. Indeed, more than 20 years ago, Mark Casson (1982) identified ‘judgement’ as one of the qualities that distinguishes the successful entrepreneur from the much larger group of non-entrepreneurial SME owners. As mentioned before, business judgement can reflect an innate ability but most frequently it directly derives from experience (or, more accurately, learning from experience). However, past experience can also filter out our ability to spot new opportunities or threats. Cultural effects related to family, locality and friends can help us interpret the world but they can also colour what we see. The same may be true of the influences from various networks that business owners often belong to (ranging from business associations such as Chambers of Commerce, business clubs and so on, to more social links related to, say, sport or leisure activities). And, of course, our own expectations and motivations of what we hope for in life, at work and in terms of a career will affect both judgement and business behaviour. The Open University Business Schools (OUBS) has conducted research in this area over the years. The findings from many different entrepreneurial firms, which reveal various influences and feedback loops on the owner-manager's decision-making, are summarised in Figure 2. Apart from the effects of the various influences that can affect business judgements, the main points to note are:

- Business situations consist of real challenges, constraints and opportunities that directly impact on the business performance of a firm.

- However, it is how entrepreneurs perceive these that guide their judgments and actions (which is why accurate market information, the ability to learn and experience are so important).

- Business perceptions are also influenced by personal and business motivations, peer pressures and cultural influences (it could be argued that entrepreneur's perceptions are more closely aligned with reality).

- Entrepreneurial behaviour is guided by the entrepreneur's expectations rather than a rigid set of strategic objectives (again, it may be that the entrepreneur's expectations are more realistic and, maybe, more ambitious than those of other business managers).

- The process is not static but very dynamic with feedback and signals from the market consciously and indirectly affecting later decisions and actions.

As each context and set of market signals reflect industry, regional and life-cycle influences, it is difficult to believe that each entrepreneur needs the same set of skills in order to achieve success. The model in Figure 2 reflects the uniqueness of the business situation facing each entrepreneur and the key areas where superior judgement will make a difference.

The influences and processes depicted in the model are complex but so too is the reality of entrepreneurial business. To date, researchers have not been able to identify a core and necessary bundle of attributes, characteristics or qualities that mark out successful entrepreneurs unerringly from the large crowd of business owners. However, a commonly quoted empirical and desk research study of new venture start-ups, that has stood the test of time over the past quarter-century, was conducted through the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by Jeffrey Timmons and colleagues (Timmons et al. 1977). They identified 14 important entrepreneurial characteristics of successful enterprise owners (see Box 2) which still frequently crop up in entrepreneurship research.

Box 2 Behavioural charcteristics of entrepreneurs

- drive and energy

- self-confidence

- high initiative and personal responsibility

- internal locus of control

- tolerance of ambiguity

- low fear of failure

- moderate risk taking

- long-term involvement

- money as a measure not merely an end

- use of feedback

- continuous pragmatic problem solving

- use of resources

- self-imposed standards

- clear goal setting.

Timmons admitted that few entrepreneurs would possess all traits but felt that strengths in one might compensate for weaknesses in others. Many of these characteristics are self-explanatory (such as high personal drive and energy, self-confidence and setting clear goals) and some appear to be linked. Others may be less obvious or well-known, such as money and profits being used as a measure of success compared with others but less as an end in itself. Helping you to develop the last quality in the list, the ability to set clear goals, is the ultimate objective of this unit.

Activity 3

- How many of the entrepreneurial qualities listed in Box 2 do you feel already, in the main part, apply to you?

- Which ones do you feel a need to find out more about?

- Which ones have you already identified as needing more development?

These characteristics appear consistently in other entrepreneurial research studies. For example, more than 20 years ago in a study of Irish entrepreneurs, Cromie and Johns (1983) identified achievement, persistence and self-confidence as general successful business characteristics as well as internal locus of control and commitment to the business, as the characteristics peculiar to entrepreneurs. Some of the qualities that people often find a bit obscure include tolerance of ambiguity (which basically refers to the ability to accept contradictory or unexpected evidence of something while keeping an open mind) and fear of failure (which can lead to pushy, goal-dominated behaviour but, in fact, is the opposite of need for achievement – nAch – mentioned in Section 1; the anxiety caused by the fear can sometimes be strong enough to cause the individual to deliberately bring about the failure that is feared). Low fear of failure means that the entrepreneur is prepared to risk things going wrong and can handle setbacks without being deterred (which is associated with but not quite the same thing as high nAch, where failure can lead to severe disappointment and loss of confidence). High achievement motivation is a great driving force but low fear of failure may be very useful in times of business chaos and uncertainty.

Activity 4

- Do you feel you are highly motivated to achieve?

- Are you competitive and get above average satisfaction from success in non-business areas such as, say sport or academic studies?

- Are you able to take setbacks without becoming too discouraged?

There is a tendency for high nAch people to come from very supportive backgrounds and for them to be motivated to achieve in different areas. In contrast, high fear of failure people tend to come from disrupted or non-supportive backgrounds and focus more obsessively on areas where they are more likely to achieve their goals (Kets De Vries 1977) (though they often set goals well below their actual potential in relation to the decision-making model in Figure 2, high fear of failure people would have comparatively low perceived capabilities and expectations whereas high nAch people may be a bit over-confident about their own capabilities and stretch their expectations by setting challenging targets). However, these tendencies are not set in stone and the actual experience of business can have a big effect in inducing either more caution or more confidence. Still, if you are uncertain of your own drive to succeed or your ability to persist, the wisest course of action is to consider pushing your idea as part of a team. Small groups not only provide support, they also have a wider range of abilities and skills and often come up with more considered decisions.

Perhaps a little less familiar is the quality that successful small business owners are said to have – high internal locus of control. This means that they believe that their behaviour determines what happens to them and that they can control their own behaviour. This is linked to the need for autonomy and personal independence expressed by many entrepreneurs as their prime motivation for setting up their own firms (Gray 1998). Internal locus of control has featured fairly consistently in studies on the psychological characteristics of entrepreneurs. Essentially the concept implies three separate beliefs on the part of individuals that:

- the outcome of events and situations are susceptible to intervention

- individuals can intervene and influence the outcome of situations positively from their perspective

- they themselves have the skills and capacity to intervene effectively in certain situations or to influence certain events.

The self-confidence, energy flexibility and opportunism associated with entrepreneurial behaviour suggests that entrepreneurs are individuals who are accustomed to getting involved and that they expect positive results from their involvement. In other words, they are prepared to expend energy and mental effort because they expect and often receive appropriate or, in their terms, valuable rewards. Also, they are flexible and opportunistic because they believe they have the capacity to become involved across a broad range of situations. Internal locus of control beliefs are essential to the success of self-motivated behaviour and form a central core of the entrepreneur's self-concept. However, it is equally clear that entrepreneurs will not be the only people sharing these beliefs.

Most reasonably successful students at all levels realise that their own efforts in studying have a lot to do with passing. Most people for whom sport is more than just an occasional leisure activity know the value of expending their own efforts on training and the importance of self-confidence. And in business, most chief executives and reasonably able mid-level to senior managers will be accustomed to obtaining positive responses from their personal interventions. It seems clear that people who believe that outcomes basically depended on their own behaviour and that they can control their own behaviour will generally believe that the control of events of importance to them ultimately rested internally in themselves. This is clearly linked to self-confidence and the ability to self-motivate. However, people with internal locus of control beliefs are in the minority. For many people, their lives are deeply affected by the decisions of people in more powerful positions than themselves which, in business, can include strong partners, customers and suppliers (as Porter's five-forces model has identified). Even more pervasive than the belief that powerful others exert a determining control or influence are widespread beliefs that events are determined by chance or luck. Activity 5 provides you with an opportunity to see where you currently stand (but note that locus of control beliefs are also influenced by context and can vary over time, especially if success breeds success).

Activity 5

Complete the Entrepreneurial attributes: locus of control questionnaire (clicking on 'Launch in a separate player' will allow you to enlarge text). This will give you an estimate of your own locus of control belief profile and what dominates – internal, external or chance.

Click on one of the three choices, depending on whether you agree or disagree with each statement, and your scores for Internal, External and Chance will appear in the respective boxes.

These concepts have been found to be useful in analysing the behaviour and beliefs of successful entrepreneurs. If you feel you scored too low for your own liking, this is another indication that a team approach may be best. Indeed, Activity 5 could also be useful in developing a balanced entrepreneurial team (not everyone can be leader with a firm belief in their ability to control destiny; opportunity often springs from being open to luck and chance happenings and most good teams rely on some members being prepared to follow more powerful others). If you want to boost your feeling of internal locus of control, one suggestion would be to set yourself attainable objectives and push yourself to achieve them. However, it is important to bear in mind that psychological scales and tests of this kind only ever measure tendencies (not absolute and immutable behaviour that holds in all circumstances) and never attain anything like 100 per cent accuracy. And, in any case, personal belief and motivation is only one part of the entrepreneurial equation.