2 What do we know about recent climate change?

2.3 Contested science: a case study

For complex issues such as global climate change, there are many opportunities for scientists to take issue with the findings of their colleagues. They can disagree about the procedures for gathering data, the completeness or coverage of the data, how the data are analysed and interpreted, and then finally the conclusions. The assumptions that shape a particular piece of research and inform the kind of questions that will be asked can be no less contentious than the quality of the data gathered.

Such contention is not unique to climate science, of course. Fuelled in part by very human concerns such as a desire to protect one's reputation, competition for funding, etc., vigorous debate is the lifeblood of science; it helps to drive further investigation and innovation. In scientific areas where society has pressing concerns, however, influences beyond the normal cut and thrust of scientific debate come into play. Scientists are typically aware of the potential policy implications of their research, and may shape their work accordingly. Often, such research is stimulated or funded by organisations with an interest in the outcome of the policy debate. In turn, interest groups and policy makers tend to adopt a ‘pick n'mix’ approach to the available scientific evidence, promoting research that reinforces their existing arguments and beliefs, and neglecting or criticising more uncomfortable findings. Equally, the influence of individual scientists sometimes owes more to their access to decision makers or the media than to the reliability of their knowledge.

In short, the science associated with policy-sensitive areas like climate change is almost bound to be hotly contested, with disputes within the scientific community being extensively reported by the media. In the early years of this century, the ‘hockey stick’ reconstruction (Figure 24b, first published by Professor Michael Mann and colleagues in Nature in 1998) became the target for a sustained (and at times, vitriolic) attack that had a high public profile in the US. This is not altogether surprising. It is a potent image – and has become, for some, an icon of what we are doing to the climate. Equally, we should bear in mind the political circumstances of the day. Shortly after he took office in 2001, President George W. Bush withdrew the US from the Kyoto Protocol on the grounds that it would harm the US economy. Given the link between fossil fuels, CO2emissions and economic activity, this is a legitimate concern; it may well be shared (privately) by other world leaders. Nevertheless, rejection of this landmark agreement to curb CO2 emissions from industrialised countries set the tone for the Bush Administration. It was widely seen as hostile to any mandatory cutbacks in CO2 emissions, and open to the influence of sceptical scientific opinion on global warming – either directly (Figure 27) or through the activities of various business-backed lobby groups.

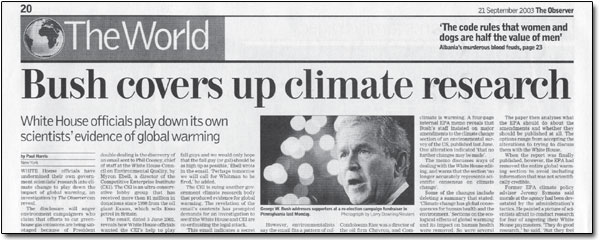

Figure 27: In September 2003, The Observer reported allegations that White House officials had sought to interfere with a report from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in order to play down the message that climate change is a serious problem.

With this background in mind, you should now tackle Activity 1. At its heart is a scientific challenge to the ‘hockey stick’ reconstruction, and the key conclusion based on it (i.e. that the warmth of the last few decades has been extraordinary), in a paper by Sallie Baliunas and Willie Soon of the Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics, published in the scientific journal Climate Research in 2003. At the time, the authors were two of the more visible scientific sceptics of the link between climate change and human activities (in the US, at least). The controversy generated by this challenge is a good example of how the science and the politics of climate change have become inextricably interlinked, and the implications that has for communicating the range of thinking on this issue. The Activity should get you thinking about the points raised earlier in this section. It also serves to identify some themes and questions that are taken up later on.

Activity 1

You should allow 2 hour(s), 0 minute(s).

This Activity is based around the first part of the BBC Radio 4 mini-series ‘Climate Wars’ broadcast in the UK in January 2004. The programme charts the genesis and fate of the research referred to above, how it became a cause célèbre in Washington, and the highly inflamed debate that followed. It gives you a chance to hear some of the scientists involved talk about their own work, together with some of the more influential sceptical voices in the climate debate in the US at the time.

Have Figure 24 to hand while you listen to the programme, and be ready to take notes that will help you to jot down your thoughts on the following questions at the end.

- How did Baliunas and Soon go about their research? What questions did they ask of the proxy data records? And what was their main conclusion?

- What were the main points in Mann's rebuttal of the paper by Baliunas and Soon? What issues were raised about the publication of this paper?

- Why did the work by Baliunas and Soon have such a big political impact in Washington?

- William O'Keefe is president of the George C. Marshall Institute, a Washington-based think tank. What appears to be the main agenda of this organisation in the climate change context?

- What was the main point at issue in the row over the report from the EPA referred to in Figure 27?

- The National Assessment on Climate Change was a US government-sponsored report that assessed (among other things) the impacts of climate change for different regions across the country. What criticisms were levelled at this report? What was particularly disturbing about attempts to have the report withdrawn?

- Myron Ebell is one of the directors of the Competitive Enterprise Institute in the US – a business-backed lobbying organisation dedicated to the principles of free enterprise and limited government. How would you characterise his stance on the global warming issue?

Answer

-

Basically, Baliunas and Soon sought to re-establish the ‘conventional’ view that the Northern Hemisphere experienced a ‘Medieval Warm Period’ (put at AD 800 to AD 1300 in their study), followed by a ‘Little Ice Age’ (1400 to 1900). They did this by asking a series of questions of the proxy data records for particular regions:

- Was there a period (of 50 years or more) with one type of climate anomaly (e.g. unusual warmth) between 800 and 1300?

- Was there a similar period with the opposite type of climate anomaly (e.g. unusual cold) between 1400 and 1900?

- How did anomalies in the past compare with 20th century climatic conditions (e.g. was it warmer during Medieval times than it is today, etc.)?

- The main point in Mann's rebuttal was the one we emphasised in Section 2.2.2. To challenge his (and the IPCC's) conclusions, any re-analysis of the proxy data record would have to show that disparate regions during the same 50-year period experienced simultaneous warming similar to that observed during the second half of the 20th century (when warming has been happening almost everywhere). Baliunas and Soon did not do this; they simply found evidence for a patchwork of different 50-year warm periods in different parts of the globe. In short, their conclusions did not follow from the evidence they presented. One of the editors of Climate Research (Professor Hans von Storch) made it clear that this ‘flaw’ was picked up during the journal's peer-review process (see <PreviousNext>